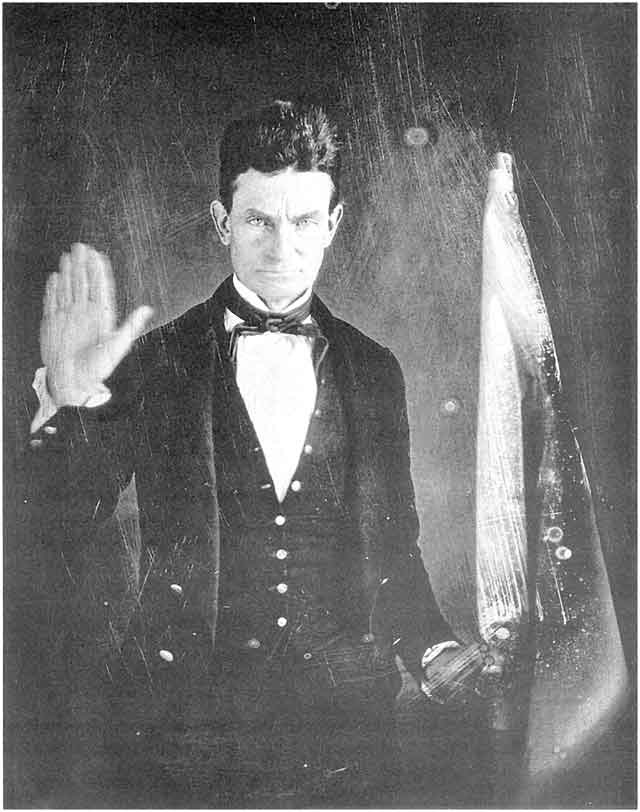

In honor of Independence Day, I decided to write a bit about one of my all-time favorite Americans, who happened to have been, for all intents and purposes, a terrorist (much like one of my other heroes, Geronimo).

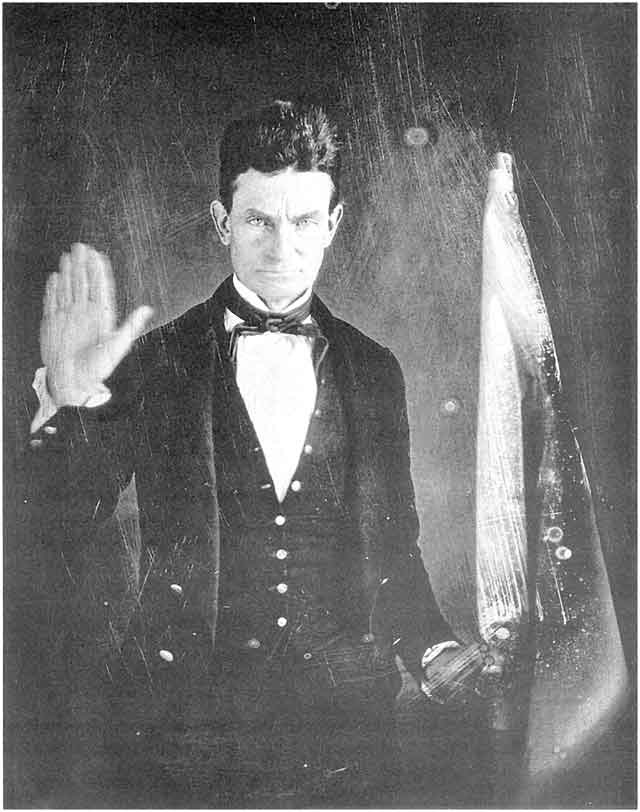

I’m talking about ‘Ossawatomie’ John Brown, the man Herman Melville called “the meteor of the [civil] war.”

Many more qualified people can argue the finer points of the causes of the American Civil War. They may say it was the last throes of agrarian society against the industrial revolution, or the assertion of the invidual represented by the southern states against the conglommerate, as characterized by the northern union, and there may something to say for all of these arguments.

But the plain fact of the matter is, whatever the myriad of causes that lead up to it, the powder keg was set off because of slavery, as clear cut a case of right vs. wrong as the Allies vs. the Axis.

And the hand that lit the match was John Brown’s.

Brown was born in Connecticuit in 1800, the son of Owen Brown, the founder of Oberlin College in Ohio.

He was raised in a strict Cavinist household. The Calvinist Christian doctrine teaches that the natural state of man is wicked depravity, that his very nature makes him incapable of redemption or ascendence to the divine. Only with God (and this is the concept known as sovereign grace) can a man find redemption. This is, not by individual merit or effort; God has chosen from all of eternity, an Elect few who are predestined from birth to receive grace and reward. The rest will be subject to God’s wrath. This has the effect (I believe) of putting a man on constant eggshells. If every soul that will receive reward is already accounted for, how does one know if, when they die, they will go to heaven or hell? They don’t. If a man lives a worthy life, it is because God wills it. And only he knows at the end of his life if he was one of the Elect. The same goes for a wicked man. If a man does evil, he is in his natural state. If that same man repents and becomes a righteous person, it is because he was one of the Elect all along, unless he’s only paying lip service to appear good, in which case he was damned all along anyway and is just play acting for whatever reason.

Now I write about this to try to give you a sense of what went into the volatile mixture that was John Brown.

Now I write about this to try to give you a sense of what went into the volatile mixture that was John Brown.

In addition to this unique religious upbringing, he was a poor tanner’s son, in a region of the united states where the native population outnumbered the whites. As a result, he grew up in buckskins and counted native boys among his best friends. What effect this had on the racial notions of young John Brown can only be guessed, but he was raised in a fiercely abolitionist household. Now most northerners were nominally abolitionists, that is, they were opposed to the idea of slavery.

Brown had first hand experience with it.

Mainly self reliant, by the age of twelve he drove a herd of his father’s cattle to Michigan and stayed at the house of a family friend. There he observed a black boy his age savagely beaten with an iron shovel and made to sleep in the cold wearing only rags and tatters. In his own words, this made him “swear eternal war on slavery.”

In 1837, after trying and failing at numerous business ventures, Brown and the rest of the country bore witness to an escalation in pro-slavery and abolitionist conflict when the Reverend Elijah P. Lovejoy, an outspoked abolitonist minister who published an anti-slavery paper called The Alton Observer (perhaps unwisely, in the midst of the pro-slavery town of Alton, Illinois, which was a known base for slave catchers), was gunned down by a pro-slavery mob.

Upon hearing of the murder in church at an anti slavery meeting, Brown rose from his pew and announced to the congregation;

“Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

Frederick Douglass

He spent four years in Springfield, Massachussetts, trying his hand at the wool trade and helping to establish the city as a major stop on the Underground Railroad. Commiserating with fellow abolitionists, he befriended prominent African Americans of the time like Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, the latter of which said, after dining and sleeping in Brown’s home,

“…while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition. My utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man’s strong impressions.”

Thereafter, relocated Brown family (he had fathered twenty children on two women – his first wife had died) to the black community of North Elba in upstate New York, where he worked for several years to improve the conditions, and also ran a station on the Underground Railroad, ferrying escaped slaves up into Canada.

In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, which opened the western territories of the same name to settlement, and left the question of whether Kansas would be admitted to the Union as a slave or free state up to the voting residents. This had the effect of inducing pro and anti slavery forces to send droves of settlers into the state to swell their respective ranks. In what became known as ‘Bleeding Kansas,’ sporadic armed conflicts began to erupt between the opposing factions. This was the civil war in its adolesence, with junior bushwhackers and jayhawkers playing out in miniature what would rage across the entire union in a few short years.

Among the anti-slavery residents, a few of Brown’s grown sons had settled and begun organizing and arming the abolitionist-minded settlers. Writing to their father of their concern for the safety of themselves and their families, the family patriarch responded by moving west, stopping along the way at several of his own haunts, soliciting money and arms from like-minded abolitionists (Brown carried crates of .54 Sharpes rifles hidden in crates marked ‘bibles’ – these became the so-called Beecher Bibles, named for prominent abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher). He and his sons became local leaders of the anti-slavery militia.

In May of 1856 three things conspired to bring the conflict to a head for Brown. His father died, the unofficial anti-slavery capitol of the territory, Lawrence, was sacked by pro-slavery ‘Border Ruffians’ under the sanction of a corrupt sheriff, and on the floor of the Senate, Charles Sumner of Massachussetts was beaten with a metal tipped cane by Senator Preston Brooks of South Carolina, after Sumner said in a scathing anti-slavery oration of Brooks’ relative Andrew Butler;

“Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight. I mean the harlot Slavery (and went on to insinuate that pro-slavery senators were pimps and that the main southern cause for championing slavery was so the lecherous masters could force themselves on negro women).”

Southern Chivalry – the Caning of Senator Sumner

In a rage, Brown called together his sons and a few militia members and taking up broadswords and rifles, raided the homes of five pro-slavery settlers along the Pottawatomie Creek, dragged the men out into the night, hacked them to death, and shot them.

From then on, Brown and his sons became guerilla fighters, even raiding into Missouri to liberate slaves from the auction block. They clashed with Missouri militias, defending the Kansas settlement of Palmyra and turning back a superior force for a time at Ossawatomie (earning him the nickname ‘Ossawatomie Brown’). One of Brown’s sons, Frederick, was killed in the latter fight.

In late 1856, Kansas governor John W. Greary ordered an end to hostilities, offering amnesty to both sides upon the cessation of conflict. Brown and his surviving sons headed East to raise funds for the cause.

The cause, for Brown, possibly unbeknownst to some of his wealthy, pacifist backers, was to wage total war on the South and incite servile insurrection on a mass scale. Brown had been germinating this plan since his introduction to the Underground Railroad.

Nat Turner

For inspiration, he looked to Spartacus, the Thracian gladiator who trained and commanded an army of slaves against the Roman Empire, and to Nat Turner, the black preacher who in 1831 led 56 slaves in an armed uprising in Southhampton, Virgina which resulted in the deaths of 160 whites and blacks, and his own eventual capture and execution. Brown was also spiritually inflamed by the figure of Moses in Exodus (whose likeness he even took on in his later years, cultivating a long white beard) and Cinque, who led the slave mutiny on the Amistad.

His plan was to raid a federal arsenal of its stores, and march across the south, arming slaves and burning plantations as they went, looping up into the Adirondack Mountains to establish a free and separate colony of freed blacks.

After months of meeting and preparation, Brown gathered together a force of 18 men (including his sons Watson, Owen, and Oliver), including free blacks and one fugitive slave. Ready to enact his plan, he paid one last call on Frederick Douglass, asking him to come along to inspire the slaves to come to him. Douglass and Brown argued through the night, Douglass trying to convince his old friend that the plan was doomed to fail. In the end, he refused.

On October 16th Brown led his band into Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, and successfully and bloodlessly took the armory, cutting the telegraph wires and taking several wealthy landowners (including George Washington’s great grand nephew) hostage. Things took a turn for the worse however, when a black baggage master, Hayward Shepherd, was shot by one of the raiders and a train passed through the town, spreading word of the action to the surrounding countryside. Local militias descended on the town and began a firefight that lasted three days.

Dangerfield Newby

During the siege, Dangerfield Newby, a mulatto and the oldest of the insurrectionists, who had joined Brown in the hope of freeing his wife and children still in bondage in Warrenton, Virginia, was shot through the throat by a six inch spike (the town militia, unable to use the armory ammunition, was firing anything they could stuff down the barrels of their muskets). The enraged townsfolk mutilated his body, cutting off his arms and legs and taking his ears for souvenirs.On his body was found a note from his wife;

BRENTVILLE, August 16, 1859. Dear Husband.

I want you to buy me as soon as possible for if you do not get me somebody else will the servents are very disagreeable thay do all thay can to set my mistress against me Dear Husband you not the trouble I see the last two years has ben like a trouble dream to me it is said Master is in want of monney if so I know not what time he may sell me an then all my bright hops of the futer are blasted for there has ben one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles that is to be with you for if I thought I shoul never see you this earth would have no charms for me do all you Can for me witch I have no doubt you will I want to see you so much the Chrildren are all well the baby cannot walk yet all it can step around enny thing by holding on it is very much like Agnes I mus bring my letter to Close as I have no newes to write you mus write soon and say when you think you Can Come

Your affectionate Wife HARRIET NEWBY

On the morning of the 18th, Brown and his remaining defenders and their hostages were surrounded in the town firehouse by the US Marines, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, future General of the Confederate Army, and Lt. JEB Stuart, destined to win renown in the coming war. Under a white flag, Stuart parleyed with Brown, offering to spare his life if he surrendered. Both of his sons lying dead behind him, Brown declared “No, I prefer to die here.” Whereupon the Marines smashed the engine house foors with sledgehammers and charged in firing. Brown was wounded, and Lt. Israel Green, who had borne his dress sabre into battle, inadverdantly spared him when his blade bent on Brown’s belt buckle.

On the morning of the 18th, Brown and his remaining defenders and their hostages were surrounded in the town firehouse by the US Marines, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, future General of the Confederate Army, and Lt. JEB Stuart, destined to win renown in the coming war. Under a white flag, Stuart parleyed with Brown, offering to spare his life if he surrendered. Both of his sons lying dead behind him, Brown declared “No, I prefer to die here.” Whereupon the Marines smashed the engine house foors with sledgehammers and charged in firing. Brown was wounded, and Lt. Israel Green, who had borne his dress sabre into battle, inadverdantly spared him when his blade bent on Brown’s belt buckle.

Of the 18 raiders, eleven were killed, three escaped, and four were captured and sentenced to hang.

Brown’s raid was a total failure.

Yet, in the last three months of his life, the attention of the world turned to his trial. I can only liken it to the importance of the Rodney King hearings. The entire world held its breath. The liberal minded could not fathom that America could allow Brown to be executed, and the south was enraged by the notion that a terrorist attack on American soil could possibly be expected to go unpunished.

Victor Hugo wrote letters urging Brown’s pardon. Predicting the civil war, he wrote,

“Let America know and ponder on this: there is something more frightening than Cain killing Abel, and that is Washington killing Spartacus.”

Henry David Thoreau likened him to Christ.

And Brown, despite his failure as a commander and businessman, did not fail in the last, to use the national attention he had engendered to speak out against slavery at every turn. In his cell, he responded to slews of letters and interviews, denouncing slavery as the greatest sin of the nation, and speaking out against slaveholders, pro-slavery politicians, and southern clergy who dared to condone the institution, whether directly or by inaction.

He comported himself magnificently at his trial. When his defense attorneys decided to plea insanity, Brown himself refused the motion. When he was sentenced to hang, he is recorded as saying;

“Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

“Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to “remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.” I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done.”

In the last months of his life, abolitionist conspirators and supporters of Brown planned and prepared to execute a rescue plan. When a former compatriot of Brown’s, Silas Soule (who would heroically go on to testify against the horrible Sand Creek Massacre of Cheyenne Indians in Colorado, and later be murdered for it), managed to infiltrate the prison and tell Brown of the plan, Brown flatly refused to be rescued. He had decided he would do more for the cause of abolition as a martyr than as a fugitive.

It’s this singularity of purpose that I can’t help but admire. Here was a man who rose up at precisely the right moment and became the lynchpin of history. Abraham Lincoln is remembered as freeing the slaves, but how could there be an Emancipation Proclamation without the Civil War, and how could there be a Civil War without the selfless actions of John Brown, a man who perceived a wrong so abominably terrible in American society that he couldn’t abide it, and was unwilling to simply wait out what most beleived would be a natural, gradual end.

How could a man of that time step forward and put his life on the line for a people society taught were not his own? Was it his Calvinist sense of predestination? Or was it that he took all he had been taught, in terms of the laws of God and man, as serious and literal as it was meant to be? Why is John Brown a footnote in history, that the majority of people don’t even know about? Was it because he was a white man? I don’t believe his crusade was as much about race for him as it was about class oppression. Was it because his solution to a nationwide injustice perpetuated and accepted in society was violence?

How could a man of that time step forward and put his life on the line for a people society taught were not his own? Was it his Calvinist sense of predestination? Or was it that he took all he had been taught, in terms of the laws of God and man, as serious and literal as it was meant to be? Why is John Brown a footnote in history, that the majority of people don’t even know about? Was it because he was a white man? I don’t believe his crusade was as much about race for him as it was about class oppression. Was it because his solution to a nationwide injustice perpetuated and accepted in society was violence?

His favorite Bible passage after all was Hebrew 9:22 – And almost all things are by the law purged with blood; and without shedding of blood is no remission.

People called him insane, and fanatical. But in my mind he was the only sane man in an insane world. He was witness to one of the most barbarous and pernicious practices our country has ever visited upon human beings, and he saw it for precisely what it was, an abomination, an affront to everything America was intended to stand for. He was the man who stood up and said no to what most people were content to ride out or pretend wasn’t happening, or write a check for and forget about. The man took up arms in an unwinnable personal crusade, and sacrificed himself and his sons on the infamous altar of liberty, if ever any man did (“I could live for the slave,” Frederick Douglass wrote, “John Brown could die for him.”). If this is insanity, then the insane should be given freer rein in this world.

Interestingly, Malcom X said of John Brown, on this very day, in 1965;

“You know what John Brown did? He went to war. He was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. White people call John Brown a nut. Go read the history, go read what all of them say about John Brown. They’re trying to make it look like he was a nut, a fanatic. They made a movie on it, I saw movie on the screen one night [I assume this was Raymond Massey in either Seven Angry Men, or Santa Fe Trail – he played him twice] . Why, I would be afraid to get near John Brown if I go by what other white folks say about him. But they depict him in this image because he was willing to shed blood to free the slaves. And any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom—in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts. . . .So when you want to know good white folks in history where black people are concerned, go read the history of John Brown. That was what I call a white liberal. But those other kind, they are questionable.”

“You know what John Brown did? He went to war. He was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. White people call John Brown a nut. Go read the history, go read what all of them say about John Brown. They’re trying to make it look like he was a nut, a fanatic. They made a movie on it, I saw movie on the screen one night [I assume this was Raymond Massey in either Seven Angry Men, or Santa Fe Trail – he played him twice] . Why, I would be afraid to get near John Brown if I go by what other white folks say about him. But they depict him in this image because he was willing to shed blood to free the slaves. And any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom—in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts. . . .So when you want to know good white folks in history where black people are concerned, go read the history of John Brown. That was what I call a white liberal. But those other kind, they are questionable.”

In reading about him, the sheer complexity of coincidence surrounding him is astounding. As he sat upon his coffin and was wheeled out to the gallows in the back of a wagon, 2,000 soldiers were amassed to secure the scene. Among them, amazingly, was another future Confederate hero, Stonewall Jackson, and an actor who had borrowed a militia uniform solely to attend the hanging. This man expressed satisfaction at the abolitionist traitor’s fate, but grudgingly admired Brown’s stoic courage when faced with his own mortality.

His name was John Wilkes Booth.

It’s as if all of history were poised about him.

Brown left a handwritten note with the executioner. It read;

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

He was right. Following his hanging, the outcry on either side of the spectrum was too intense and inflammatory to settle down. Southerners theorized that Brown’s bloody raid had been part of a Black Republican conspiracy to undermine the south. Why else would a white man risk his life to free slaves? The liberal north demonized the south as Pharisees enacting another crucifxion. The south was appalled at support for Brown’s actions, which they saw as traitorous. It was as if the entire Muslim population of America had come out for Osama Bin Laden (they didn’t, in case you didn’t know that). The first whispers of secession were heard.

And Frederick Douglass (who I think, may have turned the tide of Brown’s personal fate had he agreed to join him, for not a single Virginia slave flocked to his side) said famously;

“But the question is, did John Brown fail? Did John Brown draw his sword against slavery and thereby lose his life in vain? And to this I answer ten thousand times, No! No man fails who can so grandly give himself and all he has to a righteous cause. If John Brown did not end slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery. When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone -the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union -and the clash of arms was at hand. The South drew the sword of rebellion and thus made her own, and not Brown’s, the lost cause of the century.”